The Lumber Room

The children were to be driven, as a special treat, to the sands at Jagborough. Nicholas, in trouble, was not to attend. Only that morning he had refused to eat his bread-and-milk claiming there was a frog in it. Older and wiser people had told him that there could not possibly be a frog in his bread-and-milk and that he was not to talk nonsense; but he continued and described in great detail the coloration and markings of the frog. “You said there couldn’t possibly be a frog in my bread-and-milk; there was a frog in my bread-and-milk,” he repeated, with the insistence of a skilled tactician who does not intend to shift from favorable ground.

So, his boy-cousin and girl-cousin and his younger brother were to be taken to Jagborough sands that afternoon and he was to stay at home. His cousins’ aunt, who insisted in calling herself his aunt also, had invented the Jagborough trip in order to impress on Nicholas the fun that he had given up by his disgraceful conduct at the breakfast-table.

It was her habit, whenever one of the children misbehaved, to create some special trip from which the offender would be left out; if all the children sinned collectively they were suddenly informed of a circus in a neighboring town, a circus of unrivalled merit and uncounted elephants, to which, but for their depravity, they would have been taken that very day.

As the party drove away the aunt commanded, “You are not to go into the gooseberry garden.”

“Why not?” demanded Nicholas.

“Because you are in trouble,” said the aunt loftily.

Nicholas did not admit the flawlessness of the reasoning; he felt perfectly capable of being in trouble and in a gooseberry garden at the same time. It was clear to his aunt that he was determined to get into the gooseberry garden, “only,” as she remarked to herself, “because I have told him he is not to.”

Now the gooseberry garden had two doors by which it might be entered, and once a small person like Nicholas slipped in there he could basically disappear from view amid the growth of artichokes, raspberry canes, and fruit bushes. The aunt had many other things to do that afternoon, but she spent an hour or two in trivial gardening operations among flower beds and shrubberies, where she could keep a watchful eye on the two doors that led to the forbidden paradise.

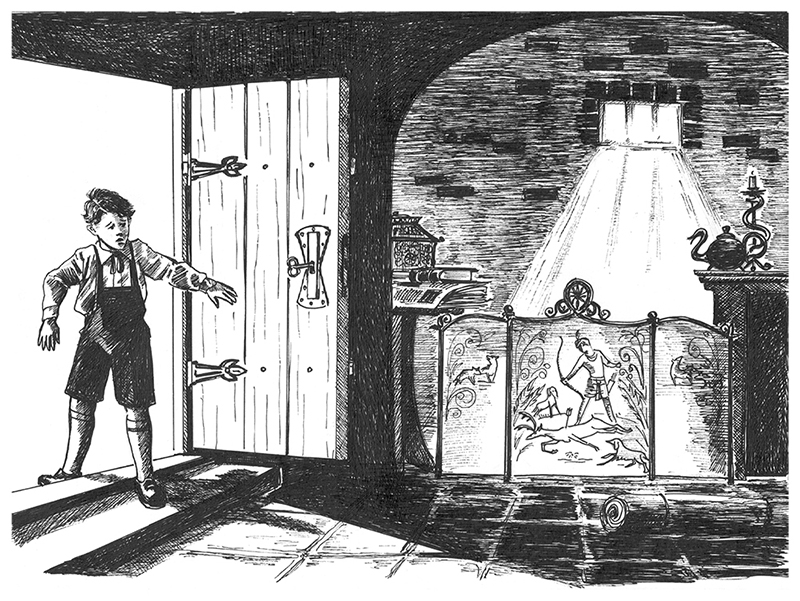

Nicholas made one or two trips into the front garden, wriggling his way with obvious stealth of purpose towards one or other of the doors, but never able for a moment to evade the aunt’s watchful eye. As a matter of fact, he had no intention of trying to get into the gooseberry garden, but it was convenient for him that his aunt believe that he had; it was a belief that would keep her busy for the greater part of the afternoon. Having thoroughly confirmed her suspicions Nicholas slipped back into the house and rapidly put into execution a plan of action that had long developed in his brain. By standing on a chair in the library one could reach a shelf which held a fat, importantlooking key. The key was as important as it looked as it kept the mysteries of the lumber-room secure from unauthorized intrusion. The key turned stiffly in the lock, but it turned. The door opened, and Nicholas was in an unknown land.

Often Nicholas had pictured what the lumber-room might be like, it was so carefully sealed from youthful eyes and about which no questions were ever answered. It lived up to his expectations. It was large and dimly lit, one high window opening on to the forbidden garden being its only source of light and was a storehouse of unimagined treasures. The aunt was one of those people who think that things spoil by use and consign them to dust and damp by way of preserving them.

The parts of the house Nicholas knew best were bare and cheerless, but here there were wonderful things for the eye to feast on. There was a piece of framed tapestry that was evidently meant to be a fire-screen. To Nicholas it was a living, breathing story; telling of a story of a huntsman in some remote time period. Nicholas sat for many minutes reliving the possibilities of the scene.

There were other objects of delight and interest claiming his instant attention: there were twisted candlesticks in the shape of snakes, and a teapot fashioned like a china duck, out of whose open beak the tea was supposed to come. How dull and shapeless the nursery teapot seemed in comparison! And there was a carved sandal-wood box packed tight with aromatic cotton-wool, and between the layers of cotton-wool were little brass figures, hump-necked bulls, and peacocks and goblins, delightful to see and to handle. Less promising in appearance was a large square book with plain black covers; Nicholas peeped into it, and, behold, it was full of colored pictures of birds. And such birds! In the garden, and in the lanes when he went for a walk, Nicholas came across a few birds, of which the largest were an occasional magpie or wood-pigeon; here were herons and bustards, kites, toucans, tiger-bitterns, brush turkeys, ibises, golden pheasants, a whole portrait gallery of undreamed-of creatures. As he was admiring the coloring of the mandarin duck and assigning a life-history to it, the shrill voice of his aunt caught his attention. She had grown suspicious at his long disappearance, and had leapt to the conclusion that he had climbed over the wall behind the screen of the lilac bushes; she was now engaged in energetic and rather hopeless search for him among the artichokes and raspberry canes.

“Nicholas, Nicholas!” she screamed, “you are to come out of this at once. It’s no use trying to hide there; I can see you all the time.”

The angry repetitions of Nicholas’ name gave way to a shriek, and a cry for somebody to come quickly. Nicholas shut the book, restored it carefully to its place in a corner, and shook some dust from a neighboring pile of newspapers over it. Then he crept from the room, locked the door, and replaced the key exactly where he had found it. His aunt was still calling his name when he sauntered into the front garden. “Who’s calling?” he asked.

“Me,” came the answer from the other side of the wall; “didn’t you hear me? I’ve been looking for you in the gooseberry garden, and I’ve slipped into the rain-water tank. Luckily there’s no water in it, but the sides are slippery and I can’t get out. Fetch the little ladder from under the cherry tree —”

“I was told I wasn’t to go into the gooseberry garden,” said Nicholas promptly. “I told you not to, and now I tell you that you may,” came the voice from the rainwater tank, rather impatiently.

“Your voice doesn’t sound like aunt’s,” objected Nicholas; “you may be the Evil One tempting me to be disobedient. Aunt often tells me that the Evil One tempts me and that I always yield. This time I’m not going to yield.”

“Don’t talk nonsense,” said the prisoner in the tank; “go and fetch the ladder.” “Will there be strawberry jam for tea?” asked Nicholas innocently.

“Certainly, there will be,” said the aunt, privately resolving that Nicholas should have none of it.

“Now I know that you are the Evil One and not aunt,” shouted Nicholas gleefully; “when we asked aunt for strawberry jam yesterday she said there wasn’t any. I know there are four jars of it in the store cupboard, because I looked, and of course you know it’s there, but she doesn’t, because she said there wasn’t any. Oh, Devil, you have sold yourself!” He walked noisily away, and it was a kitchenmaid, in search of parsley, who eventually rescued the aunt from the rain-water tank.

Tea that evening was partaken of in a fearsome silence. The tide had been at its highest when the children had arrived at Jagborough Cove, so there had been no sands to play on — a circumstance that the aunt had overlooked in the haste of organizing her the expedition. The tightness of Bobby’s boots had had disastrous effect on his temper the whole of the afternoon, and altogether the children could not have been said to have enjoyed themselves. The aunt maintained the frozen muteness of one who has suffered undignified and unmerited detention in a rain-water tank for thirty-five minutes. As for Nicholas, he, too, was silent, in the absorption of one who has much to think about; as he imagined the treasures hidden in the lumber room.